Group Size

?

1.) Small group (teams of 4-6)

2.) Individual Task

3.) Large Group

4.) Any

Small group (teams of 4-6)

Learning Environment

?

1.) Lecture Theatre

2.) Presentation Space

3.) Carousel Tables (small working group)

4.) Any

5.) Outside

6.) Special

Carousel Tables (small working group)

QAA Enterprise Theme(s)

?

1.) Creativity and Innovation

2.) Opportunity recognition, creation and evaluation

3.) Decision making supported by critical analysis and judgement

4.) Implementation of ideas through leadership and management

5.) Reflection and Action

6.) Interpersonal Skills

7.) Communication and Strategy

1Creativity and Innovation

2Opportunity recognition‚ creation and evaluation

5Reflection and Action

7Communication and Strategy

Objective:

Introduction:

For students of Forensic Science, the ability to identify and assess multiple plausible solutions to a given problem is essential as is the ability to separate the objective facts of a problem, from the subjective interpretation of those facts.

For students of Forensic Science at Glyndwr University, these skills are nurtured and developed through the undergraduate programme.

Once such activity challenged students to propose potential timelines, mapping the order in which circumstances unfolded, in a real life case. Students worked in teams to identify every possible sequence of events, considered error to rank the likelihood of potential sequences, and through the format of a debate, presented their findings, arguing either for the guilt or innocence of the suspect, subject to cross-examination from the audience.

The session was delivered to a group of approximately 20 students in the second year of their academic study, as a 2-hour, classroom based session.

Activity:

Pre-Activity

Introduction (0 – 20 minutes)

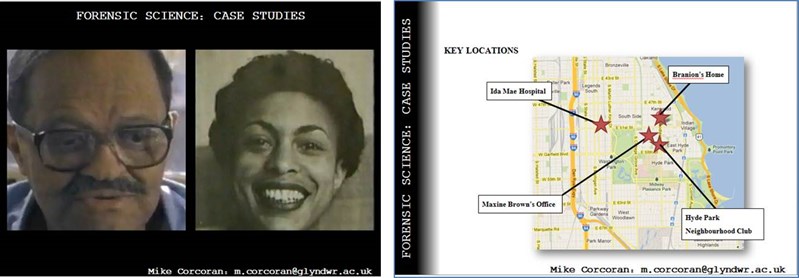

Figure 1. Slides from presentation

These questions were;

Time-lining (20 – 60 minutes)

Debate (60 – 100 minutes)

Conclusion (100 – 120 minutes)

Post activity

Impact:

The session not only developed skills, knowledge and understanding relevant for a Forensic Science context, but broader enterprising skills, through generating, developing and reflecting upon solutions to problems, and presenting and defending these solutions to an audience. These skills equipped students for all of their future endeavours.

Learner outcome:

Students were well engaged throughout the two-hour session, and all reported enjoying the activity. The practical nature of the activity supported the learners in retaining the key information from the case for their assessment, and the wide variety of learning contained within the session (lecture based / video / group work / debate / group research), ensured the session remained fast-paced and was well suited to all learners.

The exercise helped the students to better understand the danger of over interpreting evidence, how to split the objective from the subjective, and offered experience in identifying and testing numerous potential solutions to a given problem.

Resources:

References: